The other day a friend sat down with me in his old, but cozy apartment which he shares with a hamster and a bird; where you have to go outside to get to the bathroom and where the walls and shelves are decorated with crosses and other religious symbols. My friend is a very religious man. He said that he’d have to tell me something.

He, a man with wide shoulders and a massive beard, was visibly afraid to do so, so I got a little scared as well. He stammered and stuttered and I only got that it had something to do with love and sexual orientation and since he was constantly looking at the small parrot sitting by his side with seductively red cheeks I got a little worried what the bird’s got to do with it. “I have been in a relationship for 6 years”, he said. “But it is strange.” He gulped and it was a very uncomfortable situation: him, me and the bird. “Because my partner is a He.”

You cannot picture my relief. “How is that strange?!”, I asked, knowing that it was a rhetorical question, but I was happy that the bird was left out of the game for good. “Well, this is the Balkans”, he said. “It is very strange.”

“But I don’t want to see it” – Invisibility of a marginalized group

The friend and I met during a conference in Macedonia, he lives in Serbia. The conference was all about European values and EU integration and the participants were rather open-minded young people from all over the Balkans. Still, while everyone easily found common ground discussing the importance of social entrepreneurship and the battle against corruption, the core values of an “open society” were neglected. My friend did not feel comfortable to come out to anyone but two other gay men (not even to me by that time), because of constant derogatory comments about the LGBT community by participants. As open minded as it get would be: “I don’t mind people being gay, but I don’t want to see them in the streets.” (Which really is just another way to slily hide your homophobic attitude of which you secretly know that it’s not okay).

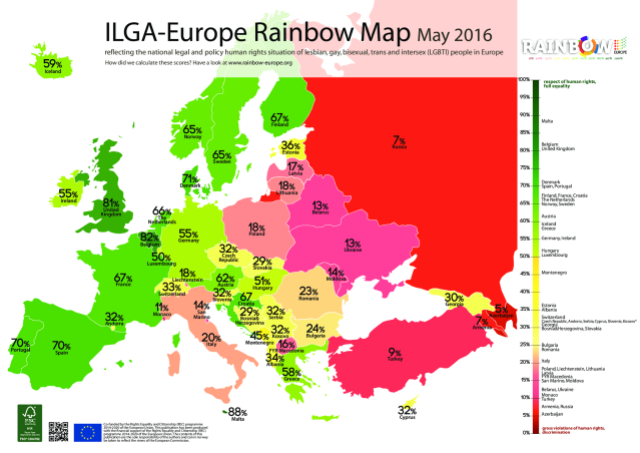

The Balkans are, to say it bluntly, not a good environment for members of the LGBT community. The ILGA – Europe Rainbow Map (2016 Index) shows that, on a scale from 0% to 100% (and 100% meaning full equality), Western Balkan countries mingle somewhere in the lower third: Bosnia & Herzegovina gained 29%, Serbia 32% and the worst picture depicts Macedonia with only 16%.

I kind of throw the Western Balkan countries in one big pot here, because the discriminatory experiences of people belonging to the LGBT community are similar in all countries (collaboration between countries is also considered crucial for successful changes by NGOs in the sector). While my friend’s personal story draws a picture of life in urban Serbia, I set my main focus on the case of Macedonia since this is the country from where I have gathered the most information.

In Macedonia a study (2016) by the National Democratic Institute (NDI) finds that 89% of the population find equal marriage unacceptable. Hate speech is on the daily agenda of the public media and 3 out of 6 members of the national Commission for Protection against Discrimination have previously expressed homophobic, islamophobic and misogynist views. The NDI also finds that 66% of LGBT people surveyed experienced verbal harassment or abuse and 27% experienced physical violence. Young people with same sex sexual orientation are 50% more likely to commit suicide than their heterosexual peers. It is difficult to measure the actual threats of LGBT persons in the region since the data is dealing with high rates of denial as well as relying on personal perception.

What’s wrong with me? Coming out in a closed-minded community

So, let’s take a look at young people, growing up, trying to figure out their sexuality (which is confusing enough for all teenagers anyways) only to realize that they are “strange”, because they are not the norm. “I thought I might be one of 10 weirdos from Serbia”, my friend said. “Because LGBT are invisible and nobody is really trying to change that. You might never get in touch with LGBT topics if you don’t try to.” And who would try to, especially from an open-minded, unbiased perspective?

When my friend grew up the internet was not really around yet, making it impossible to get in touch with online communities and platforms. That has changed, making it easier for young people to search for support, friends and answers online. The prejudices and stereotypes and the deep-rooted belief by society that homosexuality is a free choice to burden oneself or to burden someone else have still changed only little.

Knowing that you are not the only one in your country to be different might make it easier to accept your own sexual orientation and to stop the daily denial, the fake heterosexual relationships and the constant lies to yourself – but it does not make it easier to be, as in the case of my friend, a gay man. Acceptance of this sexual orientation – maybe discounted as just another “phase” – by family, friends and the always judgmental neighbours is most of the times low. You might find a new family among the LGBT community. But often the best option seems to just stay in the closet and try to adjust. Just to be safe.

Hiding in the closet

When my friend realized that he is just not into girls, he begun to study Italian in order to emigrate to Italy at some point. His plan was to escape his family. He loved his girlfriend at that time, but at the same time happy that she was very traditional and insisted on not engaging in any sexual activity until marriage which obviously was much in his favour. When talks about marriage started to be serious he broke up with her. “It was enough that I lied to myself, I did not want to ruin her life as well.” He decided to become a monk and went to a monastery where he enjoyed the prayers, the singing and the work. It was during his time in the monastery when he had his first crush on another gay man who also showed him that he, or they, are by far not the only ones in Serbia. He switched monasteries twice, until his last abbot, a gay man as well, gave him his blessing. “It was the first time that somebody told me that my sexual orientation is not a sin.” My friend left the monastery and started to study, ready to live a normal life.

He is in a relationship since 6 years, his parents refuse to meet his boyfriend (even though he has lived with them until recently when he found an apartment cheap enough to afford). He and his boyfriend only act like a couple, hold hands or kiss in dark side alleys, at home or when on vacation, constantly hiding from haters or potential offenders. He maintains two Facebook profiles, one for the people he meets at conferences, through work or whatsoever – and one where he can be just himself and share and like LGBT content. His boyfriend, working in a public institution – hence a highly homophobic environment – has been married before, divorced his wife, and is a loving father to his kids. Nobody knows about his sexual orientation, not even his mother. He doesn’t want to put his job at risk or bring his children or ex-wife in an uncomfortable situation, exposing them to discrimination and bullying. My friend stays in his hometown in Serbia, even though he hates it often enough. “I love him. I cannot be without him.” It’s love, what can you do?

Resistance to accept alternative models of sexual orientation and gender identity is huge

In the case of Macedonia members of the LGBT community should technically be able to enjoy their full rights. Macedonia has signed and ratified all relevant international conventions. The Macedonian constitution ignores this topic though. Not only does it not specifically mention the right to free sexual orientation in the according anti-discrimination paragraph. Furthermore the parliament voted in January 2016 “in favour of constitutionally defining marriage as a union solely between a man and a woman.” (ILGA annual country report 2016).

In Macedonia, similar to other countries of the (Western) Balkans, low levels of knowledge about LGBT issues and plenty stigmas and stereotypes combine with a “high degree of resistance to conferring equal rights and opportunities based on sexual orientation and gender identity” (NDI report 2015). This makes it very difficult for (young) people to get out of their isolation and firstly accept their own sexual orientation or identity to then secondly make these topics visible and engage in activism. Yet another survey has found that 51% of parents say they would look for a cure if their child would not be heterosexual. Their son or daughter can be as brilliant as there is, score only the best grades and get into the fanciest programmes – but the success is not worth it if it’s not followed by the founding of a family as it is supposed to be – mother, father, child, child, dog.

Coming out in such an environment is a threat to one’s own security and happiness – but staying in the closet is not more comfortable. It is an infuriating dilemma, and at the same time heart-breaking.

Not much of a priority of most – but the movement slowly grows

After the disturbing 1990th LGBT rights have not been much on the development agenda of former Yugoslav countries, because of struggles to overcome ethnic conflict and because of the focus set on the transition and development of economic and political systems. At the same time, as seen in Macedonia, progressive policies did not get a foothold, to the contrary can one observe massive conservative and nationalist backlashes which involve focus on traditional family models and gender roles.

Still, in tiny baby steps things are changing and foreign pressure, let it be the EU or US aids, play a big part in it. More civil society organisations are trying to make the LGBT community more visible. NGOs in Macedonia have yet not managed to organize a pride parade in Skopje, but “pride weeks” with public events, discussions and exhibitions are happening annually even if not yet with a broad public recognition. Just a couple of months ago in December a memorandum was signed between the LGBTI Support Centre and the Ombudsman of Macedonia in order to cooperate on LGBT issues. An important step will be to free the community from the impeachment of being “abnormal”. The TV series “Prespav” which features next to other characters a gay couple tries to open people’s minds. It will not be easy to get rid of stigmas; the prejudices are rooted deeply in the societies of the Western Balkan where it often matters more what your neighbours think than what you yourself desire. The visibility process of the LGBT community has to go hand in hand with the growing national feminist movements. As long as a “female” or “feminine” character serves as grounds for an insult it is difficult to change further understandings of sexual orientation and gender identity.

My friend is not so optimistic about these changes, even though he does see them happening. “I try not to think about the future, it upsets me a lot. But I enjoy happy moments.”

Still, I had a conversation with a French man a few weeks ago who had met a Macedonian man in a nightclub in Skopje where they engaged in some public kissing. “People were stunned, they didn’t know what to think. But there was one girl who came up to us and gave us thumbs up. That was a good feeling.”

Research, Publications and Videos for further Information

National Democratic Institute: NDI Poll on LGBTI Issues in the Balkans is a Call to Action. (2015)

ILGA Europe: Annual Review of the Human Rights Situation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex People in Europe 2016

Subversive Front: Manual for Youth Workes. Raising Capacity in Working with LGBT Youth. (2017). This Manual gives a great introduction into different aspects of sexual orientation and gender identity and I recommend it to everyone who’s new to the topic.

S-Front: Analysis of the Anti-Discrimination Legislation in the Republic of Macedonia in Relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. (2016)

Homepage and Youtube-Channel of LGBT United. LGBT United filmed the series “(In)Visible” in four parts which gives insight into the life of members of the LGBT community in Macedonia and into activism of NGOs

The Economist: It’s Okay to Be Gay. A photo slide show by Tomislav Georgiev (collaboration with Robert Bosch Stiftung and World Press Photo). 2013.

“Prespav” breaks the stereotypes: A gay kiss represents love and it is a positive emotion (s-front.org.mk)

LGBTI Support Centre: “Signed a Memorandum of Cooperation between the LGBTI support centre and the ombudsman” (2016)